A Short History of English

In order to be able to understand the diverse nature of modern English vocabulary, it’s important to go back to the origins of the English language, at least to some extent. The original inhabitants of the birth-place of English were Celts, but their influence on the English language was severely limited, generally assumed to have only contributed a number of place names or the names of rivers, such as Avon or Thames. Earlier settlers in the area before the Celts appear to have had no influence on the language at all. And, although the Romans invaded Britain in 55 BC (and left again about 410 AD), Latin at that time didn’t really have a very strong influence on the local language, either, even though we can still see its influence in a number of place names, predominantly those ending in -{caster} or -{chester}, indicating that these places were probably originally Roman fortifications.

The first genuine roots of the English language lie in the Germanic languages of early settlers from areas around Denmark, what is now Northern Germany, and the Northern coast of the Netherlands. The first settlers were mainly Saxons, who began to settle along the Southern and Eastern coasts of modern England in the 5th century AD. These were later ‘complemented’ by the Angles (Engle), who spoken englisc (i.e. Angle-ish), which became English, the name of the language spoken in the British Isles.

In the late 6th C, Britain was increasingly christianised, which established Latin as the language used for scholarship and historical documentation, although it hardly had any influence on the spoken language.

From here on, it becomes possible to trace the developments that have affected the English language, or – to be more precise – its various dialects, more clearly. To allow you to develop a deeper understanding of these developments, we’ll try to observe the differences and potential changes in a number of different texts from the various periods up to the modern days. We’ll do so, of course, primarily related to their lexis, rather than attempting to acquire any in-depth knowledge of the exact grammar and phonology, even if these linguistic features have had obvious effects on the former.

Many of the exercises we’ll do below have a very similar format. For a given text that illustrates some of the features of the period, we’ll try to understand the language features first by looking at lists of single words or sequences of words (also known as n-grams) step-by-step before looking at the whole text. These lists will be shown in a table inside a dynamically created new window, where you can write some notes regarding the potential meaning next to each word/sequence, and also save the results to a web page that you can store on your computer to refer back to later.

As the meaning of words is usually best understood in context, this will allow us to understand what characteristic shapes the words of English may have taken at different times, how similar or different they may have been to modern-day English, and how they may have worked (morpho-)syntactically to produce meaning in context. The closer we’ll get to Modern English, the easier this should become, so don’t worry if, at first, you’ll be able to recognise very few words or constructions, but still don’t give up trying too early as this will train you to look out for and recognise different features.

Old English (ca. 750-1150)

The first text we’ll look at an extract from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, taken from Sweet’s Anglo-Saxon Primer.

- Select the number of words , starting at 1.

- .

- Study the list very closely and try to identify the meaning, gradually increasing the number of words. In analysing and attempting to identify the words, you may need to do some detective/guess work. As you go through the exercises, keep a record of your findings/ideas in the text area below. If you need to use any special letters from the text, copy and paste them, either from the word lists or the text itself.

- First, check to see whether the word may be identical to a modern-day word. If that is the case, chances are that the word hasn’t changed since then, although you may also encounter some ‘false friends’.

- Failing that, try to guess what any unfamiliar letters may sound like, and see whether this may help. Hint: maybe your knowledge of IPA transcription symbols may help...

- Next, see whether changing or removing things at/from the beginning or end of a word may help.

- Do the same thing inside the word.

- Also, if you have any knowledge of German or any Scandinavian languages, see whether you can detect any similarities.

- Next, check the box here → , and change the number back to 1, to produce a reverse-sorted list. Then, see whether you can determine any regularity in the endings and their potential meanings. Are these endings very similar or very different from Modern English?

- Finally, look at the whole text and see whether it gets easier to determine more of the meaning. Always bear in mind, though, that the aim of this exercise is not for you to be able to translate it, but to understand more about what Old English looked like.

Breten īeġ-land is eahta hund mīla lang, and twā hund

mīla brād; and hēr sind on þǣm īeġlande fīf ġe·þēodu:

Ęnġlisc, Brettisc, Scyttisc, Pihtisc, and Bōc-læden.

Ǣrest wǣron būend þisses landes Brettas. Þā cōmon

of Armenia, and ġe·sǣton sūþan-wearde Bretene ǣrest. Þā

ġe·lamp hit þæt Peohtas cōmon sūþan of Scithian mid

langum sċipum, nā manigum; and þā cōmon ǣrest on

Norþ-ibernian ūp; and þǣr bǣdon Scottas þæt hīe þǣr

mōsten wunian. Ac hīe noldon him līefan, for þǣm þe hīe

cwǣdon þæt hīe ne mihten ealle æt·gædre ġe·wunian þǣr.

And þā cwǣdon þā Scottas: 'Wē magon ēow hwæþre rǣd

ġe·lǣran: wē witon ōþer īeġland hēr-be·ēastan; þǣr ġē

magon eardian, ġif ġē willaþ; and ġif hwā ēow wiþ·stęnt,

wē ēow fultumiaþ þæt ġē hit mæġen ġe·gān.'

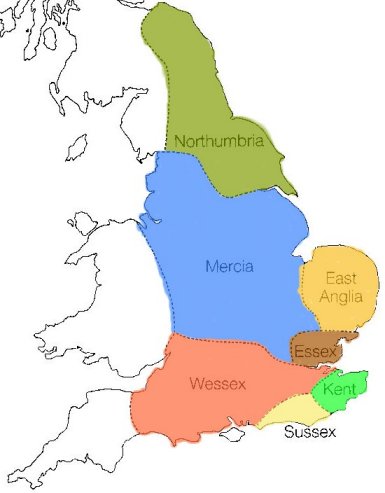

The above extract represents an example of West-Saxon, one of the main dialects of Old English. Two further major dialect areas were the kingdoms of Northumbria and Mercia, both presumably representatives of Anglian dialects. A fourth, perhaps somewhat less important one, due to its geographical limitation, is Kentish. The map below (adapted from Trudgill, 1990) shows the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms about a hundred years before the ‘official’ start of the Old English period, where (roughly) later areas ending in -{sex} can be assumed to have become part of the West-Saxon dialect area, while East Anglia would presumably have been part of the Mercian area.

For examples of Northumbrian and Mercian, and how they differed from the above, you can take a look at the page on Historical Linguistics from my Introduction to English Linguistics course. Here, you’ll also encounter some similar, but also a few different, symbols from the ones seen above, which were used during the Old English period, the æ (ash; probably pronounced like the modern IPA character), ƿ (wynn; pronounced /w/), þ & ð (thorn & eth; both variably representing modern <th> spelling), and the ӡ (yogh; pronounced /j/ or /ç/).

In contrasting the three dialects, another highly important feature we can observe here, and which you’ll hopefully already have spotted above while looking at the reverse-sorted list, is the strongly inflected nature of Old English. As we’ll be able to see soon, this high degree of inflection soon began to diminish, and today, English only has very few inflectional endings left, as it has become increasingly analytical. Overall, we can observe that most of the words are still very Germanic, and that there is no easily discernible influence from non-Germanic languages.

From the end of the 8th century, invaders from Norway and Denmark came to raid and to settle in what later came to be called the Danelaw. This area of Skandinavian influence ended just above Essex on our map in the South-East, with the dividing line to the West-Saxon area running roughly through the bottom half of Mercia towards the North-West. The important influence of these Skandinavian settlers on the language, however, is not easily traceable in the writings of the Old English period, mainly because it seems to have predominantly affected the spoken language at first. Skandinavian words, such as give, take, call, die, sky, law, husband, skin, knife, etc., which form an essential part of daily-life vocabulary, can only be documented based on the writings from the Middle English period.

In Old and Middle English, the diversity in the different ‘standards’ can be assumed to have caused many more problems in communication between people from different areas than it would today, despite the common Germanic core that the Anglo-Saxons and Skandinavians shared, simply because there was no agreed standard (or lingua franca) for communication.

Middle English (ca. 1150-1500)

Towards the Middle English period, if anything, dialect diversity increases further, so that often communication between people from different areas would have become even more difficult. In order to illustrate and understand the diversity, we’ll analyse two examples of Middle English literature, in the same way as we analysed the Old English material above. One of these is an example of the written dialect of the (Northern) West Midlands, and one from Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, both written in the late 14th century.

| Excerpt from ‘Sir Gawayn and the Grene Knyght’ | Excerpt from Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, ‘The Physician’ |

|---|---|

|

|

|

Bot Arthure wolde not ete til al were serued, He watʒ so joly of his joyfnes, and sumquat childgered: His lif liked him lyʒt, he louied þe lasse Auþer to longe lye or to longe sitte, So bisied him his ʒonge blod and his brayn wylde. And also an oþer maner meued him eke Þat he þurʒ nobelay had nomen, he wolde neuer ete Vpon such a dere day er hym devised were Of sum auenturus þyng an vncouþe tale, Of sum mayn mervayle, þat he miʒt trawe, Of alderes, of armes, of oþer auenturus, Oþer sum segg hym bisoʒt of sum siker knyʒt To joyne wyþ hym in justyng, in jopardé to lay Lede, lif for lyf, leue vchon oþer As fortune wolde fulsun hom, þe fayrer to have. |

With us ther was a DOCTOUR OF PHISIK; In al this world ne was ther noon hym lik, To speke of phisik and of surgerye, For he was grounded in astronomye. He kepte his pacient a ful greet deel In houres, by his magyk natureel. Wel koude he fortunen the ascendent Of his ymages for his pacient. He knew the cause of everich maladye, Were it of hoot, or coold, or moyste, or drye, And where they engendred, and of what humour. He was a verray parfit praktisour: The cause yknowe, and of his harm the roote, Anon he yaf the sike man his boote. |

- Compare the language of the two extracts with regard to their spelling and grammar. In which way do they differ from Modern English?

- Check the box here → , and change the number back to 1 again, to produce another reverse-sorted list of either of the two Middle English texts, and see whether this gives you any further clues.

Despite the initial diversification in the Middle English dialects, communication became easier towards the end of the 15th century. Standardisation of the written language began around the time that Caxton introduced printing to England in 1476, and with the increasing availability of printed materials, based around a ‘courtly standard’, the opportunity for more and more people to learn how to read and write according to more accepted and fixed norms made communication easier.

As you will hopefully have noticed from the exercise involving the reverse-sorted list, the number of endings is already greatly reduced in this period, with most of them already taking on a relatively more familiar form. What is perhaps still striking is the occurrence of final <e> in verbs and adjectives, where we no longer encounter these in Modern English. In terms of the origin of the words, whereas essentially all of the words in the Old English text were of Germanic origin, we can now see an increasing influence of words derived from French, Latin, or Greek. Regarding the spelling, the Gawain extract still exhibits a very common feature attributed to the influence of French writing, which is that the letters <u> an <v> could be used interchangeably.

Today, it is still sometimes wrongly assumed (by non-linguists), though, that the French influence on English started with the Norman Conquest in 1066, but initially, the influence the French invaders had on the language spoken in Britain remained severely limited because there was very little interaction between the British and their invaders, with the latter still ‘looking towards the continent’ for most aspects of cultural life, and both groups speaking their own languages amongst each other. Thus, it was only in areas where interaction between the ruling class and the ‘nether folk’ was absolutely necessary (even if some noblemen may actually have been bilingual), that French had any influence on English in those early days, e.g. in the areas of food or French governance. It was only in the mid-thirteenth century, after the Normans had lost their estates in Normandy (in 1204), that French words began pouring in by the thousands, affecting the areas of social life & hierarchies (e.g. duke, count, nobility, people, peasant), the legal system (e.g. judge, justice, jail, divorce, evidence), government (more than before; e.g. crown, sovereign, duty, empire), warfare (e.g. war, arms, warrior), Christian ethics (complementing/partly replacing Latin terms; charity, devotion, conscience, virtue), the arts (e.g. romance, story), trade (e.g. carpenter, mason, merchant), household articles (e.g. carpet, curtain, couch, table), clothing (e.g. coat, gown, robe), etc. Notwithstanding the important influence of French, the core language, i.e. the words that occur with the highest frequency or most commonly, still remained Germanic.

Words form Latin or Greek in this period mainly related to science, as they still do today, and can be considered part of a somewhat more learned vocabulary. This is especially evident in the Chaucer extract above. It’s not always clear, though, whether some of these words may not have been ‘imported’ via French at the time, rather than directly from Latin.

Early Modern English (ca. 1500-1700)

The Early Modern English period is mainly known as the age of playwrights and poets, such as William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, Ben Jonson, John Donne, Edmund Spenser, etc. Here, the language is already much closer to Modern English in most respects, although we can still observe some differences.

The following excerpt from John Donne’s poem The Canonization illustrates some of the main points of interest.

- As before, select the number of words , starting at 1, and increasing it step-by-step.

- .

- Try to identify the meaning of the words and what their similarities and differences to modern English may be, employing the same techniques for modifying the words, as necessary.

FOR God's sake hold your tongue, and let me love;

Or chide my palsy, or my gout;

My five gray hairs, or ruin'd fortune flout;

With wealth your state, your mind with arts improve;

Take you a course, get you a place,

Observe his Honour, or his Grace;

Or the king's real, or his stamp'd face

Contemplate; what you will, approve,

So you will let me love.

Alas ! alas ! who's injured by my love?

What merchant's ships have my sighs drown'd?

Who says my tears have overflow'd his ground?

When did my colds a forward spring remove?

When did the heats which my veins fill

Add one more to the plaguy bill?

Soldiers find wars, and lawyers find out still

Litigious men, which quarrels move,

Though she and I do love.

Try to identify and describe the features of the above text that make it different from modern English texts, even poems.

The influence of the classical languages, Latin & Greek, increased again around 1530, partly because some authors unfortunately considered the English language to be too impoverished to be of literary value, so that they sought to augment the vocabulary through direct borrowing from these languages, something which even affected the grammar to some extent. Quite rightly, though, soon people came to object to this practice, dubbing those imported words inkhorn terms, and complaining that these made the language incomprehensible. Both languages, however, experienced further ‘revivals’, especially during the Renaissance, where unfortunately the general perception was that in the ‘Golden Age(s)’ everything was better and should be seen as a model, and of course through their continuing use in scholarly terms, although English had already come to replace Latin as the language of science and the church.

Sources & Further Reading:

Algeo, J. & Pyles, T. (2005). The Origins and Development of the English Language (5th edition). London: Arnold.

Berndt, R. (1984). A History of the English Language (2nd edition). Leipzig: VEB Verlag.

Knowles, G. (1997). A Cultural History of the English Language. London: Arnold.

Trudgill, P. (1990). The Dialects of England. Oxford: Blackwell.

Strang, B. (1970). A History of English. University Paperbacks. London: Methuen & Co, Ltd.